Sebring - The Early Years

From War Birds to Race Cars

For most racing fans, Sebring has always been a sports car racing circuit. What they may not realize is that before auto racing this property served as a United States Army Air Force training base for B-17 bomber crews. During World War II, trained pilots and crews were sent here to transition to B-17, B-24, and B-29 bombers. Between 1942 and 1946, over 10,000 pilots and crewmen trained here, conducting over 600,000 take-offs and landings.

After the war, Hendricks Army Airfield was decommissioned and turned over to the City of Sebring on May 1, 1946. The Sebring Air Terminal was created to oversee the enormous property and find suitable ways to make it useful to the city.

Today, the sights and sounds of high-powered War Birds have been replaced with those of racing cars, but historians will continue to remember this place with reverence for its essential contribution to the war effort.

1950 - The First Sebring Race

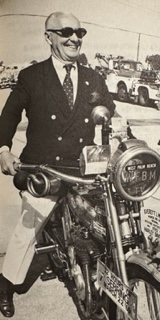

Alec Ulmann, Sebring race promoter from 1950 thru 1972.

Alec Ulmann, a Russian American aviation engineer and motorsport visionary, arrived in Sebring in 1949 seeking a location to host a European-style long-distance automobile race similar to the 24 Hours of Le Mans. Hendricks Field was ideally suited with its mile-long runways and network of interior roads providing a unique setting unlike any other track in America. An agreement was soon reached for Ulmann to work with the Sebring Firemen Inc. to launch his dream.

On December 31, 1950, Ulmann staged the first automobile race held at Sebring, the Sam Collier Memorial Grand Prix of Endurance, a modest six-hour event. A field of 28 European and American cars competed in the inaugural race under the FIA Index of Performance regulations, a handicapping formula based on engine size. The Sports Car Club of America (SCCA) conducted the race with Ulmann’s guidance.

As race day approached, Vic Sharpe from Tampa was convinced by Tommy Cole, a driver already entered in the race, that his 1949 Crosley Hotshot, with its 44-cubic-inch engine, would have a significant handicap advantage. He was right. Although many laps behind faster cars, the diminutive Crosley, driven by Fritz Koster and Ralph Deshon, was declared the winner.

Despite its humble start, the 1950 event hinted at the potential of endurance racing in America.

The First 12 Hours of Sebring

The first official 12 Hours of Sebring was held on March 15, 1952. The American Automobile Association (AAA) sanctioned the new race and ran it under FIA competition rules. This meant the car covering the greatest distance in 12 hours would be declared the winner. The new event attracted a great deal of interest. However, it drew mostly American race teams to compete.

Harry Gray and Larry Kulok claimed the first 12 Hours of Sebring victory in a Frazer Nash Le Mans Replica.

1953–1955: International Recognition

The 1953 race was a turning point, as the 12 Hours of Sebring became part of the newly formed FIA World Sports Car Championship, aligning it with global endurance races like Le Mans, Spa- Francorchamps, Mille Miglia, and Carrera Panamericana. Sebring would host the first event of the new series and enjoy its newly anointed international status.

This second running of the 12-hour race saw Phil Walters, co-driving with John Fitch in a Cunningham C4R, secure a historic victory one lap ahead of Reg Parnell and George Abecassis in a factory Aston Martin. Their win proved American engineering could compete at the highest level of motorsport.

Lancia and Aston Martin arrived with their factory teams in 1954 and would encounter strong competition from private entries from Ferrari, Jaguar, Austin-Healey, Cunningham, and OSCA. The driver entry list was loaded with international stars like Fangio, Moss, Hill, Ascari, Shelby, Salvadori, Collins, and more. The race would be full of drama. Moss remarked that the Lancias were “wiping the floor with the rest of us.” But as evening fell, so did the Aston Martins and Lancias. Sebring’s punishing circuit had defeated the fastest cars. Stirling Moss and Bill Lloyd, driving their consistent and reliable 1.5-litre OSCA MT4, emerged victorious.

The 1955 race cemented Sebring’s reputation as an unforgiving test of durability. Mike Hawthorn and Phil Walters piloted a Jaguar D-Type to victory, with Phil Hill and Carroll Shelby finishing second in a Ferrari 750 Monza Spyder.

The Birth of ARCF

The world of motorsport was shaken to its core on June 11, 1955, during the 24 Hours of Le Mans. A collision between Pierre Levegh’s Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR and Lance Macklin’s Austin-Healey spiraled into catastrophe. Levegh’s car launched into the crowd at terrifying speed, disintegrating upon impact. Its engine and debris struck spectators, killing more than eighty people and injuring many others. The shockwaves reverberated across the world.

The American Automobile Association (AAA), which had long been involved in sanctioning motorsport in the United States, immediately decided to withdraw from sanctioning international-style racing events. The AAA’s withdrawal was official by late 1955, leaving the 12 Hours of Sebring without a sanctioning body.

For Alec Ulmann, this decision was devastating. To save Sebring, he needed a solution and fast. With characteristic determination, Ulmann went to Paris in the fall of 1955 to meet with FIA officials and lay out his vision for Sebring. He emphasized that Sebring was not merely a race but an opportunity to unite American and European motorsport cultures. The FIA officials were impressed by Ulmann’s resolve. They recognized that Sebring could not be abandoned; it was too valuable to the sport. After deliberations, they granted Ulmann a direct sanction for 1956 and 1957 and approved his request to create a new sanctioning body: the Automobile Racing Club of Florida (ARCF).

As a dedicated sanctioning body for Sebring, the ARCF mirrored the structure of established clubs like ARCA and the SCCA with clear rules, regulations, and safety protocols. Under Ulmann’s leadership, the ARCF prioritized safety improvements at the track, better organization, and international cooperation—key assurances that earned the FIA’s trust. Once again, the Sebring race was an FIA World Championship event.

By the late 1950s, ARCF had become much more than a sanctioning body. It was everything Sebring. It sanctioned and promoted the race while hosting extravagant social events. Alec’s wife, Mary, was instrumental in cultivating a vibrant social scene that added a touch of glamour to the rugged Florida airfield. European aristocrats, international drivers, and movie stars further elevated Sebring’s social atmosphere making the paddock feel much like a Palm Beach social club.

ARCF is Brought Back to Life

ARCF laid dormant for over 50 years following Ulmann’s retirement until the spring of 2023 when Sebring native, Ford Heacock III, saw an opportunity to revive the organization to celebrate the history of the storied institution that is Sebring and the lasting impact on endurance racing the ACRF had.

With guidance from former Sebring race promoter Charles Mendez, winner of the 1978 race, and Sebring Race historian, Doug Morton, the Automobile Racing Club of Florida is back and quickly growing.

The newly revived ARCF now serves as the membership division of the Sebring Hall of Fame (a non-profit organization). The new club plans to host social events and educational activities for its members and to support the Hall of Fame’s mission to preserve Sebring race history. The ARCF and The Sebring Hall of Fame are also exploring the possibility of a future museum commemorating Sebring race history. ARCF Membership information is available at ARCF.net.